Understanding Stainless Steel Groups and their Machinability

What Is Stainless Steel?

Stainless steels are a type of steel alloys that have a polished appearance and offers high resistance to corrosion. These alloys are composed of Iron and a minimum of 10.5% Chromium. Most grades of stainless steel contain additional alloying elements such as nickel and molybdenum.

Chromium forms a thin layer of Cr2O3 on the surface of steel when combined with oxygen. This layer provides non-corrosive properties to the material by blocking the diffusion of oxygen to the steel surface. As a result, it prevents the spread of corrosion into the bulk of the metal.

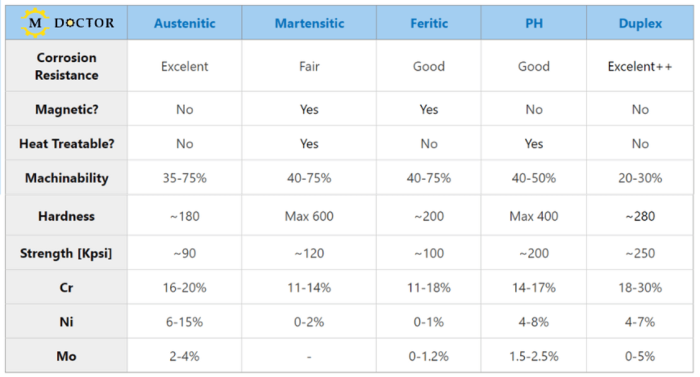

There are more than 150 different grades of stainless steel, classified into 5 sub-groups.

- Main Stainless steel sub-groups and their properties

Austenitic

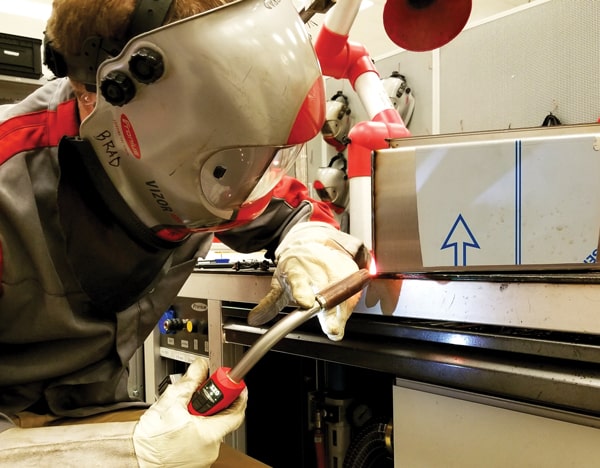

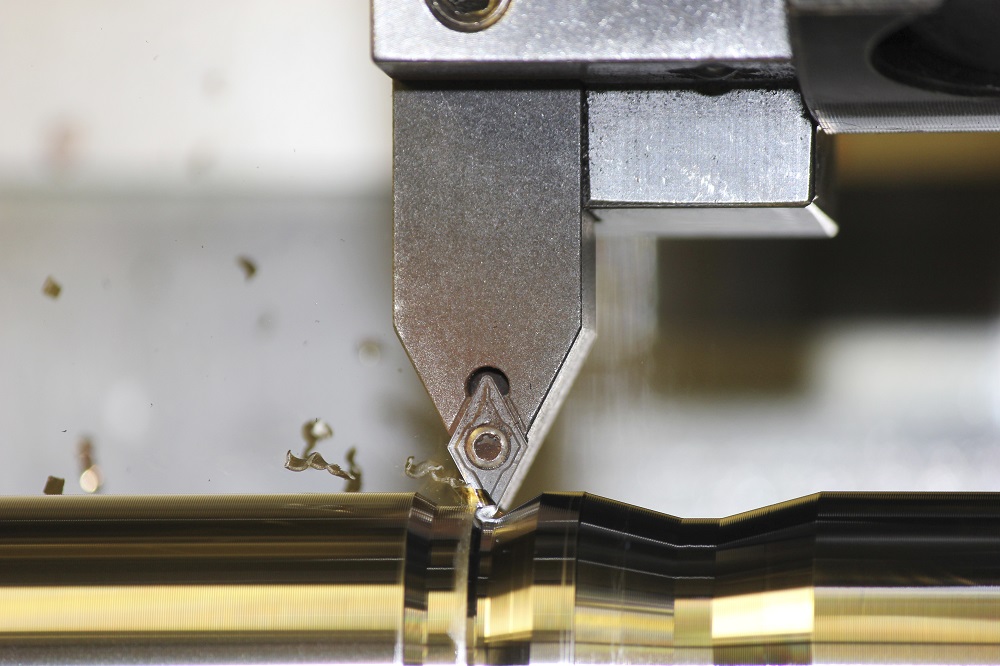

Austenitic is the most popular family of stainless steel. Characterized by a high content of chromium, up to 20%, and the addition of nickel, up to 15%, Austenitic stainless steel is known for its excellent corrosion resistance properties. However, due to the high nickel content, this type of stainless steel is the most expensive and relatively challenging to machine. Moreover, it lacks strength and hardness compared to other kinds of stainless steel. Most alloys in this series have a low carbon content, below 0.1%, which makes them ductile. Therefore, machinists should be concerned about chip control and BUE. Moreover, alloys with the suffix “L” (for example, 304L/316L) have minimal carbon content, usually 0.03%, making them even more challenging to machine.

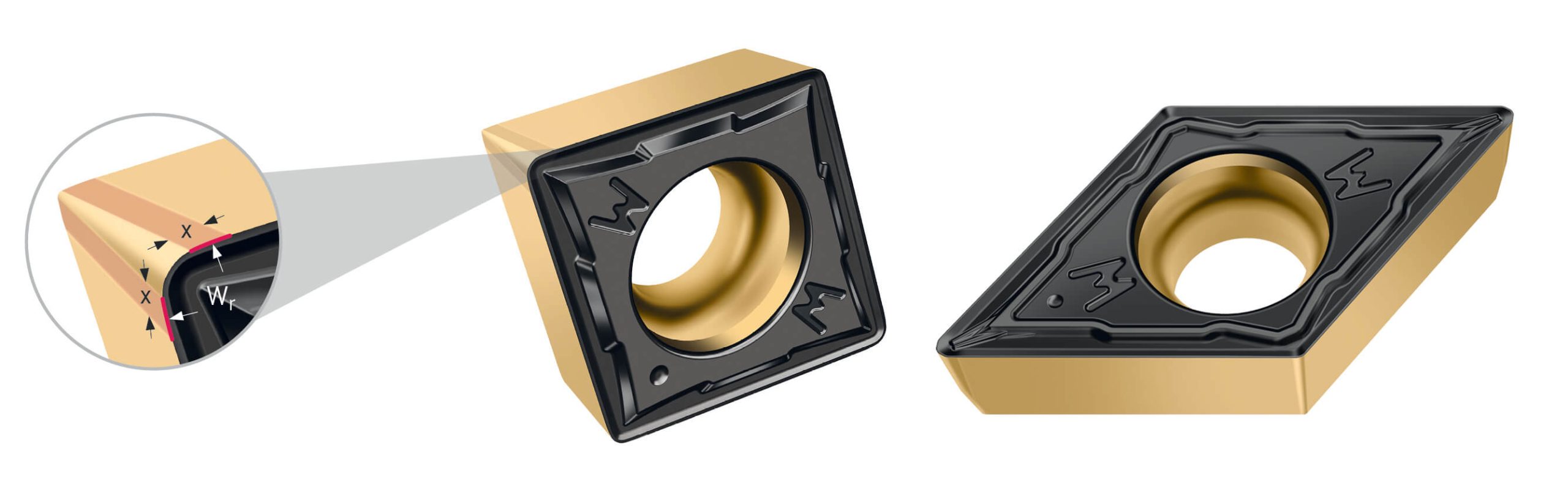

Some key challenges manufacturers face include high cutting forces, heat, and build-up edge (BUE), which occurs when the workpiece material sticks to the cutting edge. Additionally, notch wear is a common issue that can lead to high wear developing at the depth of cut line. Alloys with higher nickel and molybdenum content tend to have decreased machinability, making them more challenging to work with.

Best Practice:

- Opt for TiAlN PVD grades or thin-layer CVD grades.

- Avoid very low cutting speeds, since built-up-edge tends to form When there is not enough heat at the cutting edge.

- Use a good supply of coolant directed to the cutting edge.

- Avoid machining at a constant depth of cut to reduce the risk of Notch Wear.

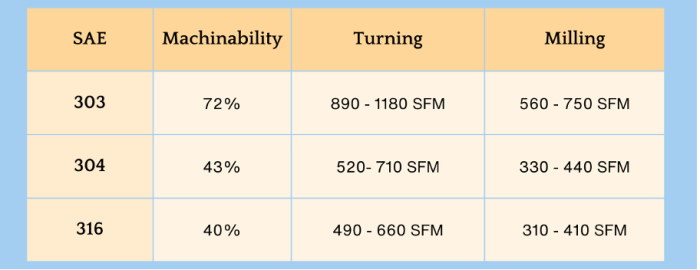

Machinability and speed recommendations for popular Austenitic alloys

Check out this complete list for more stainless steel alloy machinability.

Martensitic

Martensitic is the name of the second most popular group of stainless alloys. They have up to 14% of chromium and low nickel content. They can be heat-treated and hardened, which makes them stronger than austenitic alloys. However, they have limited resistance to corrosion and are only suitable for use in atmospheric conditions.

Ferritic

Ferritic stainless steel materials have a Chromium content of up to 18% with almost no nickel. They have better corrosion resistance than Martensitic grades but less than Austenitic ones, and they cannot be hardened by heat treatments.

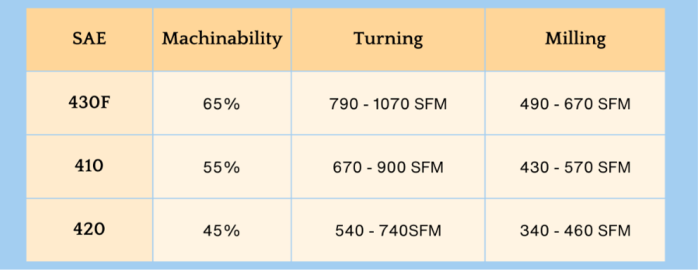

Martensitic/Ferritic Stainless is on the border between regular and stainless steel materials. Carbide grades for both Alloy steel and Stainless steel will work well on them. Typical wear is flank and crater (Like in alloy steel), with an occasional build-up edge. The machinability rate is better when compared to Austenitic stainless.

Grades with the suffix F (Like 430F/420F) are freecut materials with higher Sulfur and less Molybdenum content. This modification improves the ease of machining, yet it leads to decreased resistance to corrosion. Grades with the suffix C, such as 440C, contain higher levels of carbon, which improves their strength and hardness after heat treatment.

Machinability and speed recommendations for popular Ferritic/Martensitic alloys

Precipitation Hardness

This family, nicknamed PH, exhibits excellent corrosion resistance and can be subjected to heat treatment to achieve tensile strengths that are three times higher than typical austenitic grades. This is achieved By adding copper, aluminum, and titanium to the composition. They are extensively used in industries such as oil and gas and aerospace, where it is crucial to have high strength alongside excellent corrosion resistance.

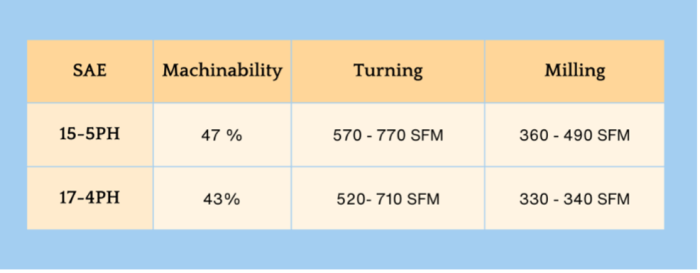

PH stainless steel alloys are available in two different conditions: annealed (condition A) or tempered (condition C). The annealed alloys have a hardness range of 20-30 HRC and are relatively easier to machine. Once machined, the parts can be age-hardened to 32-42 HRC. On the other hand, tempered (condition C) alloys are delivered with a hardness of up to 43 HRC and can be further hardened to above 50 HRC. It is important to pay attention to the condition and hardness of the alloy when determining the cutting conditions.

Machinability and speed recommendations for popular PH alloys

Duplex

This sub-group is called duplex since these materials have a two-phase Austenitic-Ferritic structure. They benefit from the advantages of both austenitic and ferritic properties, leading to increased strength, higher toughness, and broader corrosion resistance. They provide higher corrosion resistance and tensile strength than austenitic stainless. Chromium content can reach 30% (Much higher than austenitic alloys). General machining guidelines are like austenitic stainless 316, with about 20% lower machinability and more attention to clamping stability. Commercially, they are cheaper than austenitic stainless steels due to their lower nickel content. They are less widely used due to their low machinability and the fact that they lose their strength and corrosion resistance at temperatures above 570°F (300°C).

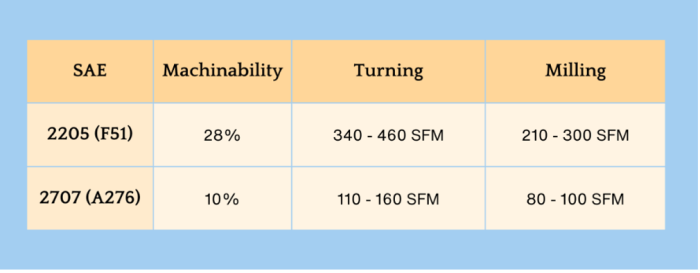

Machinability and speed recommendations for popular Duplex alloys